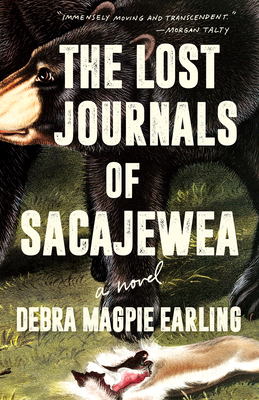

The Lost Journals of Sacajewea by Debra Magpie Earling is not your typically structured historical novel, but rather a mix of narrative poetry and prose. Sacajewea is introduced to the reader as the pre-teen and we follow her until about the age of seventeen. While most only know about Sacajewea through the context of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, Earling reframes this story from her POV as a kidnapped Lemhi Shoshone teenager who is sexually abused and assaulted, as well as forced to marry and work for a white man named Toussaint Charbonneu (who historically had multiple teen and pre-teen Indigenous wives.) Readers take note this tale carries with it a trigger warning for SA and violence. Earling’s dedication is apt for this story: “For the stolen sisters of all Native Nations.”

Earling’s depiction of Sacajewea is not the “classic American” tale of an Indigenous woman “helping” Lewis & Clark explore and expand the United States of America in their Imperialistic mission of Manifest Destiny no matter the human and environmental cost. Sacajewea is a scared kidnapped girl suffering daily to survive against the utter brutality against her and other Indigenous women. Undoubtedly, Sacajewea carries with her the words of her mother that “Men do not know Women carries a voice inside her to help her live. When you stop hearing your voice you are nothing more than snare bait.” Essentially, women have a special intuition for survival when it comes to merely existing around men. Sacajewea forms bonds with other stolen women and they try their best to support each other despite their constant exploitation and abuse at the hands of not just white men, but Indigenous men as well who seek to gain favor with the white men by essentially forcefully prostituting their wives.

Readers should be aware that this book is not structured in a traditional way, as it is predominantly narrative poetry (in my opinion.) While this style and structure is creative and beautiful, it can at times make following the plot and characters challenging. Terms and words are used that are not defined, meaning the reader must figure them out based on contextual clues. For example, I did not figure out the meaning of one word until about half way through the book. Another time I thought someone she had been interacting with was real and possibly a two spirit individual, but by the end I began to interpret this person as a spirit. Maybe I misinterpreted the “He is Woman” character incorrectly all along? I believe there may be one or two other characters who were spirits as well. Those example just encapsulate how much is left up to reader interpretation due to undefined terms, as well as vague but visceral descriptions. If you are used to traditionally formatted novels and think interpreting poetry as a narrative structure will be challenging, you may find this book hard to follow. If you accept the challenge, I encourage you to simply enjoy the unique structure and formatting and poetic narrative rather than trying to fit this story into a certain box. I also believe this book is all about reclaiming Sacajewea’s story on her terms, which is summed up toward the end with the lines, “Do not trust anyone who tells you you cannot tell your story. Do not trust anyone who tells you there is only one story. If there were only one story or one way of seeing things all stories would die.”